|

Providing Culturally Sensitive Services Dec. 2001

Imagine moving to a foreign country where you don’t speak the language, and your child gets hurt playing with another child. The injury doesn’t seem major, so you go to a traditional doctor, who treats it with herbs. When the injury doesn’t seem to be getting better, you take the child to a hospital. The doctors want to know why you didn’t get the child appropriate medical aid sooner. When you are unable to explain because of the language barrier, they become very upset. You are accused of being medically neglectful, and children’s protective services is called in. The authorities want to know how the child got injured. And because they don’t speak your language, they use an AT&T translator over the telephone. It is very hard to communicate through a translator over the phone. You have no idea how the child was hurt. She was playing. Children get hurt playing. You become frustrated with them, and they become frustrated with you. They threaten to take your child away. You go into shock. You become hysterical and break down crying, which just convinces the authorities that you are not a fit parent. Fortunately in this case Alameda County was able to

refer the Chinese family to social worker Yi Cheng. When Cheng got the

case, the child had been placed with one of the family’s relatives.

Social workers had first tried to provide voluntary services, so the child

wouldn’t have to be removed from the parents’ home, but a worker

had described the parents as uncooperative and the mother as mentally

unstable. After working with the family, Cheng found it was all a matter

of communication. And the parents, who were first assessed in very negative

terms, turned out to be model clients and model parents.

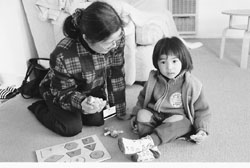

Cheng brought in Asian Community Mental Health Services.

The community agency provides comprehensive services in over 20 different

Asian languages. Working together, Cheng and Cantonese- speaking Asian

Mental Health family counselor Dorothea Ho were able to get through to

the family and piece together what happened. What happened next is not uncommon, according to Cheng. “It is very difficult to get an accurate translation, and sometimes when Asian immigrants come to the system they get frustrated and very emotional. They don’t know how to act appropriately, and the mainstream may interpret their behavior as either psychotic or non-cooperative, and basically describe them as crazy.” “We had to deal with a lot of trust issues. In

the beginning the parents were defensive, not wanting to get involved,”

Ho recalls. Although most parents are reluctant to have a government agency

involved in their personal lives, that is particularly true of immigrants,

especially those who came from countries with more authoritarian governments.

Parenting classes were the next breakthrough. Ho recalls,

“When they started going to parenting classes, they began to open.

They started talking about where they came from in China, and slowly the

feeling changed from us being strangers from an agency to friends.” Cheng explains, “I have had clients say to me, ‘Why do I have to tell this lady every week about my problems? Most of the time she just smiles and says nothing. Why do I have to tell her my private business?’ It is a very western approach and not in their culture.” And if the therapist isn’t fluent in the client’s language, the problems are magnified. For many of these clients, parenting classes can make

all the difference. These clients may feel much more comfortable in a

peer-to-peer setting, where they can have more control. It may also be

more reminiscent of a village/community, where parents might traditionally

go to their older siblings or elders for advice, rather than to government

officials. “The family became very involved in the parenting curriculum,” Ho says.“They would come to class early and actively take part in discussions by sharing their experiences and asking questions.” What particularly impressed Ho was their kindness to the other parents. As they became more comfortable, they even began bringing food to share with the class. The complexity of the issues confronting immigrants

is reflected in the parenting classes. The classes cover everything from

the stages in childhood development to cultural differences in schooling

and what to expect from the education system. The classes address racism,

including both the immigrants’ attitude towards people of other ethnic

groups and how to respond when someone makes a racial slur toward them.

The parents are given advice on how to differentiate between good and

bad American cultural influences and how to help their kids when they

get in trouble. Once the parents realized what the agency had to offer, they went from resisting to actively making use of all the services they could. Not only did they regularly attend family therapy with the daughter who was in the system, but they brought their other daughter to therapy as well. In the end the parents were very cooperative. The Dragon asked the father to comment on the family’s experience. Ho translated: “We are really thankful for all the help. It was surprising to us to have CPS involved because we thought that having two children playing together and having an injury would be pretty normal. When the children were taken away, the older one was really traumatized. Once they got back together with the family, she got better and the family grew closer together. Mrs. Cheng and Miss Ho were very helpful all along the way, with the legal issues and with home visits, making sure everything was okay.”

|

|||||||||||