Dragon Info While DCFS Burns Parenting Classes

|

Numbers Games

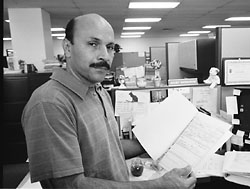

Social worker overload has been well documented. The Senate Bill 2030 workload study has determined the number of cases a social worker can reasonably service. This number is called the yardstick. Some children and family services departments, like the Los Angeles department, claim they cannot hire enough workers to meet these standards consistently. Acknowledging that they cannot meet the standards, they have negotiated caseload caps with the union. The caseload cap is the maximum number of cases a worker can be assigned. Caps are supposed to represent worst case scenarios. They signal the danger mark or red zone. Unfortunately, LA DCFS treats the cap as the norm and flagrantly violates even this agreed-upon standard. The union has filed numerous grievances, taken the department to arbitration, and won. But even after management has lost in court, it has failed to abide by the arbitrators’ rulings. Union field representative John Garfield, who handled the arbitrations, explains the caseload resolution process agreed to by management. When a worker’s caseload exceeds the cap for two months, the worker’s supervisor is required to notify the assistant regional administrator, who in turn is to notify the regional administrator. If the situation cannot be resolved, the regional administrator is to notify the department director, who is supposed to go to the board of supervisors and request the resources to hire more workers. But according to the workers we talked with, management regularly skirts the agreement. Randy Gracia, an emergency response worker at the North Hollywood office, explains: “We have a problem that has gone on for the last two years. Anywhere from five to 10 workers are continuously given cases over the caseload cap, making it impossible for them to do their work. They rotate the workers each month to make it look like they are following the agreement, but they are not.” Gracia has filed a group grievance every month for the last year. Jamal Rush is one of the workers who has filed a grievance over caseloads. “It is very difficult to complete your task if you have 40 or 45 kids. I had 40 kids this month. The cap is 37 and in the real world, according to the SB 2030 study, the cap should be 27, and 20 would be a more appropriate number for case management purposes.” “It is very difficult to complete your task... Our mission is supposed to be to protect children and strengthen families. And I don’t think you strengthen families by placing children out of the home," Jamal Rush

Rush worries that children and families are suffering. He believes that children are staying in foster care longer because workers don’t have time to do the paper work to allow the child to stay with a relative. “Our mission is supposed to be to protect children and strengthen families. And I don’t think you strengthen families by placing children out of the home.” Even when caseloads go over the cap for more than two months, management has refused to follow the resolution procedure. According to Garfield, the union documented several instances where the regional administrators did not pass monthly reports of the workers being over caseload to the board, and the department director never complied with the top step of the resolution process by asking the board to hire more line workers. Two years ago the union won an arbitration over the caseload issue in the Lancaster office. The union has met with the department at least four times to implement the settlement, and the department still has not complied. Garfield can recall only one time when the department director, Anita Bock, went to the board of supervisors to ask for more staff. She received the okay and hired 168 more administrators and management personnel. According to Los Angeles Chapter president Paula Gamboa, Bock has told workers that they are just going to have to live with high caseloads and overwork. The department has over 100 vacancies, according to union representative Harold Walker. Why won’t Bock go to the board and ask for more workers? “No department administrator wants to go to the board of supervisors and say they can’t live within their budget,” Garfield speculates.

|

||||||||